Merce Cunningham and me

I began as an indifferent musician. My mother started me on the piano when I was five, and by the time I was seven I practiced an hour a day. She gave me an allowance of five cents an hour, which I renegotiated, sometime later, to ten cents. I worked my entire childhood.

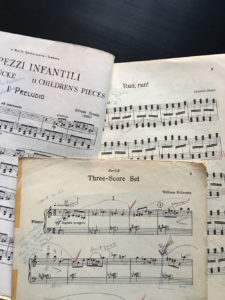

My piano teacher was a patient, kind man with thick dark-framed glasses and slicked down hair. The music he gave me was unusual and often contemporary; Persichetti, Bartok, Casella, Vila-Lobos, Pinto, Ibert, Debussy, and William Schumann. Sometimes I practiced, but often I did not. I was in love with books.

All day, I lounged reading; curled on study chairs, sprawled on the living room floor, face down on the top bunk bed late by the hallway light. As I fell asleep, I put my book under the mattress. I reached for it first thing upon waking.

One week, I decided I would read while I practiced the piano. While my mother prepared dinner, I sat in the dark living room at the Chickering upright she had gotten for free. The piano was enormous, and sat like an overstuffed chair in the corner of the room. The cracked keys had long ago sunk into the frame, and the circular piano stool creaked and rocked. Placing my novel carefully on the rack, I began to practice from memory while I read my novel. Oblivious to many of the smaller details of her children, my mother called out encouraging remarks from the kitchen as I stumbled through my pieces.

My piano teacher wasn’t as easy to fool. At my lesson, he opened the first piece I was learning. There was no obvious progress. He closed the music without comment. He opened the next piece with similar result. Five minutes in on the hour-long lesson, I slumped at the piano. He picked up his car keys, “I’ll drive you home,” he said quietly. I sat in the easy chair in the corner of the dining room and cried, what seemed, the whole afternoon.

By then, I was in love with dance. I read about early ballerinas and seeped myself in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and the great dancers Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova. I clipped magazine articles about Rudolf Nureyev and Margo Fontayne, following their every move.

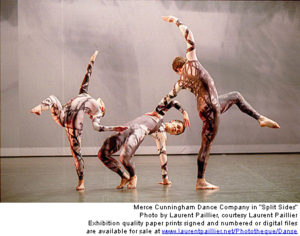

When Merce Cunningham and John Cage came to my mother’s college for a week one spring, she arranged for me to leave my sixth grade class, walk across the school playground, to the open rehearsals. I knew almost nothing about modern dance or electronic music.

There was a hush when I entered the darkened auditorium. Dancers, in leggings and sweatshirts, sprawled on the stage stretching in the dim stage lights. I walked past John Cage and David Tutor setting up their equipment. Stage lights came on and off, and a disembodied voice called down from high.

Finally, the main spotlight came on, and Merce Cunningham walked slowly into the light. Dressed in white tights and leotard, he rippled like a cat, his fawn-like face was large and luminous. I only remember the deliberate, beautiful motions, the quietness and grace.

Music has been, in part, an answer to a long call. I was born into a long line of ancestors who loved music but never did it professionally. My mother’s mother was a self taught pianist, my mother a skilled amateur violinist. My paternal grandmother’s Steinway grand piano sits in my studio; my father played jazz every evening after dinner.

Merce Cunningham opened a door in me to something I could not name. My heart softened and yielded to the essence of the purity of the moment. There was more out there than I had imagined. I came out into the quiet afternoon forever changed.

Music is also something deeper. As early as I can remember, I would lose myself for days; sometimes for months or years. Pulling back from the sharpness of the moment, I slipped into the coolness of a murky lake. The world receded, the water made the downy hairs on my face stand on end. Air escaped from my nose and the bubbles clung to my face.

Part survival, part addiction, clinicians describe this as dissociation. In the dark parts of my life, I was happy to lie down in the earth, and draw the dark wet leaves over my head. Always a peaceful, cool reprieve from what was around me, where the muffled sounds of life are no longer all absorbing.

Music has the same call to me. The hidden lake is cool and unrippling. I swoop down and fly close to the surface, almost touching the water with my body. I turn up in the air, high, into the skies, then dive down to skim the surface again. Hearing becomes everything; the rush of the wind on my cheeks, the thump of my heart, the creak of my body, and the cool of the lake. I am bodiless, just a swoop, a streak of energy; I am pure joy and delight in my own agility. As I sink into sound, I am the wind, I am the rush and the burble, I am the cool water.

Excerpted from Grief’s Grace, A Memoir by Tina Davidson