Only when a composer is true to upbringing, gender, sexuality and cultural heritage can the work be meaningful and transcend the individual.

The winter weather is icy during the Chamber Music Conference in New York City. I have been asked to meet with Annika Socolofsky, a composer, avant-folk vocalist, and fiddler, currently a graduate student at Princeton. We meet off the main hall and sit talking about being a composer, going to school and getting works performed. She pauses.

“Do you compose music as a woman?” she asks tentatively.

I smile. “How could it be otherwise?” She relaxes and nods.

This age old question, even now – as if gender is not an integral part of being. I compose what I am; a woman, daughter, mother, stepmother – a privileged well-educated white woman, older, somewhat worn, and in the last quarter of my life.

Is this still heretical?

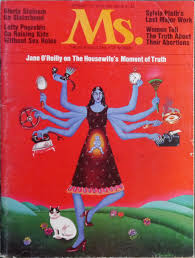

Over twenty-five years ago I wrote a widely-circulated article addressing the same question for Ms. Magazine titled Cassandra Sings (Distinctive Voices of Women Composers). Recently I reread the article with interest. Much has changed, but some things not.

Back then women were vocal about denying their gender.

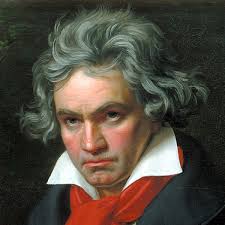

Listen to this from a well-known, Pulitzer prize winning, woman composer: “Nobody refers to Beethoven as a male composer … It’s obvious that I’m a woman and my womanhood is important to me. But I don’t write music as a woman or as a man; I write music as a composer.”

These are haunting words for they begin with a separation of self.

The issue of gender in the arts, I believe, is hidden in the concept of classical music itself.

At the heart of all this is the relationship between classical music and its extension into living culture — contemporary music. To understand the female position as a composer is to understand the classical music world.

The new music world finds its roots and past in western classical music — that of Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert and Brahms. Contemporary music is viewed as a rather unruly child. So enamored are we with classical culture, that major symphony orchestras play only about 1% of music by living composers and 99% of traditional classical music.

The figures are slightly better these days. I read online a recent article released by the Baltimore Symphony. Based on data from 89 symphony orchestras, the split is 88% classical music with 12% living composers, of which less than 2% are by living women composers. (The data catches me by surprise and I have to stop to breathe for a moment; only 2% are women composers!)

Talking about what classical music is and who wrote it, in some ways, is at the crux of women composers’ definition of self.

Classical music was written and defined by white, European, Christian males, who (insult to injury) happen to be all dead. To be exact, classical music is a male-defined aesthetic. While this in itself is quite extraordinary, it is the attitude that music is universal which is so damaging. It’s true, no one ever calls Beethoven a man, because no ever has to. He was part of the ruling class that never needs to define itself as anything more than universal, or “for all of us.” Since universal has become synonymous with male (and white), gender is omitted as it defines not yourself, but your inferiority. Thus the issue of who is speaking and what is being said is faultlessly hidden.

I am not suggesting that classical music has nothing that is relevant to this generation. Far from it. The classical music composer wrote good, honest music. He was true to his upbringing, society, place and gender. Universality can be achieved only in this way — by knowing who you are.

Oddly enough, to be universal is to speak from a deeply personal place.

All artists, no matter what the discipline, must come to find their face. Only when a composer is true to upbringing, gender, sexuality and cultural heritage can the work be meaningful and transcend the individual. If a composer prances around in someone else’s clothing, it sounds hollow and incomplete. When a composer communicates a self, which is authentic and not denied or compartmentalized, oneness between listener and artist emerges. That wonderful “ah-ha” of communication is then universal, for it is honest sharing.

I remember almost to the hour…

…when I realized that classical music was not me — I almost stopped breathing. What did this mean to me? How had my affiliations put blinders on me? In the absence of male written work, what was female? Then a wonderful feeling of excitement and delight came over me. There was so much to explore, so much to find out and it was all inside.

For instance, what is sexual energy in music? In classical music the climax (don’t you love the nomenclature?) is the culmination of rhythmic and harmonic tension. The climax arrives in a pumping, stumping, squirting fashion, collapsing into a kind of stewed silence. Now I ask you, is that me? (okay, perhaps sometimes).

But truthfully, my sexuality seems dark and powerful. It comes out of a center place and is wide, continuous, warm, moist. My physical energy is long and deeply rooted. It goes on and on, winding from one rhythm to another, slowly moving out, until, at its peak it is suddenly transformed into something else — a glowing, evanescencing energy. This, for me, is not a climax, but an epiphany.

Years later I turned my attention to being a mother, a unique and wondrous experience that rarely comes into music. My opera, Billy and Zelda, explores what I consider the greatest love story – that between a parent and child. It is the only opera I know where the main character is pregnant. (How has this story escaped contemporary opera?)

Now, I am interested in exploring myself as an older woman, this ending that is as important and, I hope, as celebratory as the beginning.

Gender is not all of what one is, but to exclude it is to lose a large part of oneself. Our journey is individual but shaded by all parts of ourselves. Complicated, complex, full of twists and turns. In the Ms. article I return to Pauline Oliveros.

But what does it matter to us, the listeners?

Pauline Oliveros, in her book Software for People, suggests that music, as it is created by men, is only half of the equation. The other half is emerging through the work of women composers. It’s not that one half is better or more important than the other, it’s just that, as Walt Whitman says, “lack one, lacks both, and the unseen is proven by the seen.” We all need both halves.

In fact, we’re entitled.

Cassandra Sings (Distinctive Voices of Women Composers), by Tina Davidson, Ms. Magazine, 1992.

Listen to music from Tina Davidson’s opera, Billy and Zelda: