I see Henry* at the conference, a wonderful composer and someone who has championed the field of new music as well as other composers. I take his elbow warmly.

Smiling, Henry turns to me from his conversation with a tall man who’s name I don’t catch. His friend interrupts our greeting. “I have to finish this conversation,” he says, and animatedly continues his long story about a job application as a composer that had not gone well.

“And then,” he finally finishes, “they hired a woman!” He pauses and names the composer. “This job was a fit perfect for my talents. Instead, they hired a woman.”

Henry knows her. “She is a wonderful composer,” he counters, “and she will be fabulous at this job.”

His friend shakes his head. All jobs are going to minority and gender diverse candidates; white men are being pushed out. I am flooded with thoughts.

I began my composing career in a music world governed by the idea of excellence – that the best candidate should get the job, the commission, or the performance. The catch, however, was who was determining this “excellence” and what the criteria was. I quickly learned that “excellence” included which school you attended, who you studied with, what kind of music you were composing, and finally, gender and race.

Fortunately, we are in a different time. Now, music institutions know that to survive they must find new connections with their audiences, as well as represent the broader community. Part of that work is to offer opportunities to minority and gender diverse composers and support those who have been hidden in the shadows.

But there is something else. Historically there have been no women composers as well known as Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms. For many reasons women were not encouraged or often ignored. But more importantly, they didn’t have opportunities to hear their music – a vital link to their growth and maturity as a composer.

Music doesn’t fully exist independent of performance. Unlike literature or art, music is incomplete until it goes under the fingers of a performer, who wrestle with translating and bringing it into life. Even then, the work is not fully realized until it is in front of an audience. Something magical happens to the work in this communication, this transfer to the ears of the listener. And it is where I learn, evaluate, and move onto the next project with increased wisdom. Without the performance of my work, my progress is hindered and only half completed.

In truth, there are always winners and losers in the face of opportunity. The pendulum sways back and forth. I have lived through the shift of dominance of university composers (mostly white men), the push for representation of women, the activation of composers in community settings, and now the inclusion of DEI. I am thrilled at where we are, and where we are moving to. This music field – this thing I love, will be greatly enhanced.

I applaud these opportunities to marginalized composers to speak, hear and learn. As their voices join with others, we cultivate a rich, diverse artistic field which will, over time, speak to and for all of us.

- Not his real name.

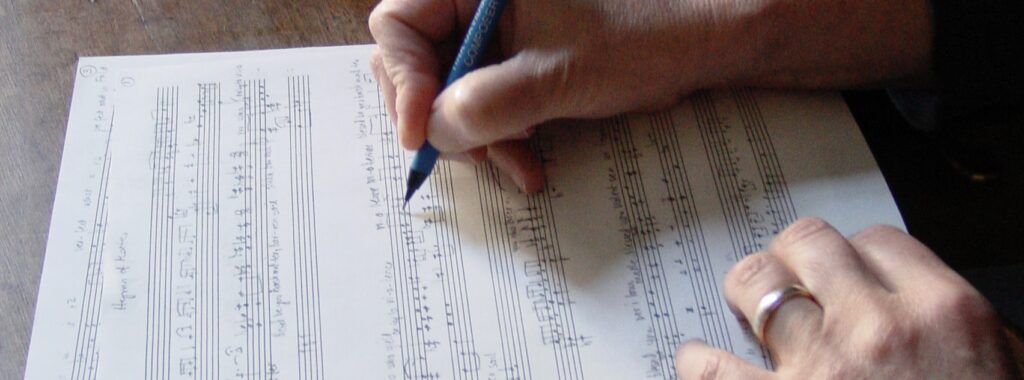

I sigh and drum my pencil on the blank score paper. All morning I have been procrastinating, unable to move forward in composing my next work. I am caught in the bardo of creation – between not knowing and, at the same time, sensing the direction of the piece.

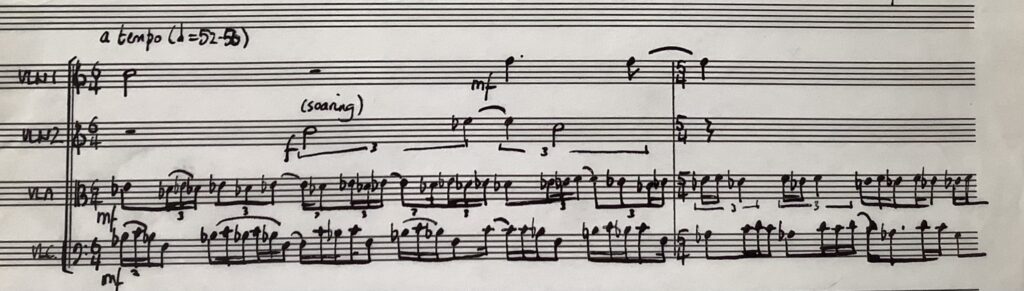

I sigh and drum my pencil on the blank score paper. All morning I have been procrastinating, unable to move forward in composing my next work. I am caught in the bardo of creation – between not knowing and, at the same time, sensing the direction of the piece. My ear is always bending towards the sound strings produce when I compose. The instrument itself is an ingenuity of construction – as one plays, the open strings resound, building up a deepening of sound – like a piano’s sustaining pedal, but discrete and selective. The resonating strings respond like ghosts to a call, building up overtones and harmonics, even different tones.

My ear is always bending towards the sound strings produce when I compose. The instrument itself is an ingenuity of construction – as one plays, the open strings resound, building up a deepening of sound – like a piano’s sustaining pedal, but discrete and selective. The resonating strings respond like ghosts to a call, building up overtones and harmonics, even different tones. sound to a bare shadow of itself by playing with the wood of the bow) gets closer to what I experience in a single note or tone – an outer shell-like-flesh with a soft inner core.

sound to a bare shadow of itself by playing with the wood of the bow) gets closer to what I experience in a single note or tone – an outer shell-like-flesh with a soft inner core.

Heave your heart into your mouth – often.

Heave your heart into your mouth – often.