In these days of growing numbers of nonbinary, gender-nonconforming and transgender people, I have been reflecting on how and why I compose music as a woman. I wince a little as I write this. It does not seem current, or perhaps currently relevant.

I came to composing over forty-five years ago when feminism was in it’s second wave, where the focus was on the inequality and discrimination of women. It was a time when women were speaking out about the marginalization of their choices and expertise, it was about being seen and counted.

My mother was the first feminist in the family. She read Gloria Steinem, Kate Millett, Germaine Greer and Betty Friedan. She taught women’s studies and went to on countless marches. True, she often spat and lectured. A professor at the State College in Oneonta, mother of five, she knew the limits of her salary and position. She had valid grievances and was angry.

My mother was the first feminist in the family. She read Gloria Steinem, Kate Millett, Germaine Greer and Betty Friedan. She taught women’s studies and went to on countless marches. True, she often spat and lectured. A professor at the State College in Oneonta, mother of five, she knew the limits of her salary and position. She had valid grievances and was angry.

I was a second generation feminist. I read Alex Katie Schulman, Erica Jong, Adrienne Rich and Alice Walker. Early on, I didn’t wear a bra or shave my legs. I worked to pass the equal rights amendment, and went on marches, taking my daughter in a stroller. Feminism, for me, was personal and deeply related to finding my voice in a male dominated music world of the late 1970s. I needed to grow myself, and I wasn’t sure how.

I am reminded of the summer I was eleven and I lived with my aunt and uncle who were scientists in Cambridge, England. One day they brought home small plates from their laboratory coated with agar, a clear medium that fuels microbes and bacteria as they grow. My job was to see what was really on our household surfaces. Carefully I took samples from the kitchen and bathroom and spread them on the agar. Uncle John pressed his thumb on one of  the plates. We waited to see what emerged. Colors bloomed several days later, a brilliant white and a poisonous looking orange – a world invisible – existing only when it was allowed to grow by itself.

the plates. We waited to see what emerged. Colors bloomed several days later, a brilliant white and a poisonous looking orange – a world invisible – existing only when it was allowed to grow by itself.

My agar medium, as I think back on it now, was feminism, or seeing myself as female. And it was Beethoven, oddly enough, who gave me permission to culture and cultivate myself.

Classical music, whose language and history I grew up in, carried forward the idea that music is ‘universal’ in its expression. In 1818, Schopenhauer wrote that music “is such a great and exceedingly noble art … a perfectly universal language, the distinctness of which surpasses even that of the perceptible world itself.” Soon came the claim that classical music works were masterpieces – above and beyond our daily lives.

This superlative description of music confounded me. Instinctively, I felt that the artistic endeavor came out of an authentic expression of myself, or as close as I could get to an inner truth. Take Beethoven, for instance. He wrote richly genuine music, an expression of who he was: a white, educated, Christian, and upper middle class. And male.

I shivered. A male aesthetic, not universal at all. And I was female.

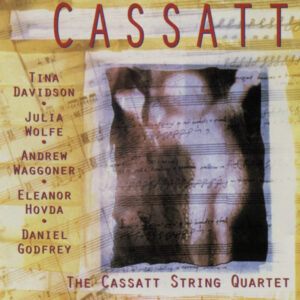

With this realization musical world opened up and works came tumbling out. While composing, I held words in my mind that related to myself and the world around me – not to create a ‘tone-poem’ or music describing a story, but as a way of exploring and understanding myself. Cassandra Sings, commissioned by the Kronos String Quartet, was both the anguish of the Greek prophetess who was never listened to or believed, and my hope for better times in the future. Women Dreaming, for mixed ensemble and piano, was my continued dreaming of possibilities. River of Love, River of Light, a seven movement choral piece, was my understanding of the female face of God.

of the Greek prophetess who was never listened to or believed, and my hope for better times in the future. Women Dreaming, for mixed ensemble and piano, was my continued dreaming of possibilities. River of Love, River of Light, a seven movement choral piece, was my understanding of the female face of God.

Feminism was, in an odd way, my lucky break. In pushing forward to illuminate the wealth of the individual, giving credibility to the female gender, I found my agar plate. It was a rich medium to explore myself, to grow my work from the hidden secrets of my inner and outer surface. To press my thumb down, and see what was revealed by my print.

After a decade of composing, I softened. I became more digested and reformulated; more fully mixed. My interest began to shift from an inner to an outer relationship to the world, and my gaze looked upwards. What was the connection to the larger whole, to the sky, earth, to the unnamable? From these eyes that belong to a woman?