My finger tips have hardened and softened after years of playing the piano. Both instinctive and learned, the fingers use multiple points of contact, never actually on the tip, but turning the pad inward a bit, or slightly to the side. The thumb is a special case and is used on the length of it’s side where the muscle is less dense, and closer to the bone. Loud dynamics are produced by stiffening up the whole hand so it can bear the weight of the arm, or even engaging the back; soft sounds take more muscle restraint. Recently at a concert, I saw a brilliant young pianist stab the keyboard with stiffened fingers to create a percussive depth of sound, then bending her back, using loose wrists, her fingers whispered a soft rapid phrase.

stiffening up the whole hand so it can bear the weight of the arm, or even engaging the back; soft sounds take more muscle restraint. Recently at a concert, I saw a brilliant young pianist stab the keyboard with stiffened fingers to create a percussive depth of sound, then bending her back, using loose wrists, her fingers whispered a soft rapid phrase.

The piano is an odd instrument. Considered by some as a percussion instrument, because of it’s mechanical nature and the broad inner harp of strings, it is the only classical instrument that uses both hands and the weight of the body to create sound in a skin to note manner. String instruments use one hand to finger, while the other holds the bow, which alone creates the dynamics and nuances of the sound. In the winds and brass, it is breath that creates sound and dynamics, while the fingers lift and close the note holes. Percussion instruments use mallets, and some of the drums use the flat of the hands, even fingers at times, to coax out the sound. Finally, the harp; while both hands are used to pluck the strings, the body, wedged behind the spine of the instrument, cannot move.

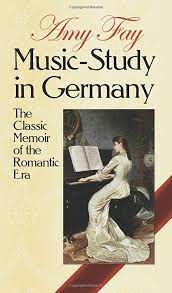

Piano technique has a long and rich history. During Bach and Mozart’s time, the keyboards were light to the touch. Performers used what was know as the “finger action” school, where the arms were relatively fixed, and the fingers skittered along. As the piano evolved with a wider range of volume, the touch became heavier. Pianists and composers such as Chopin and Liszt began to use the weight of the arm, playing with a supple wrist; this became known as the “arm weight” school of technique. I love the description that Amy Fay, a student of Liszt, wrote in 1902, “When Liszt played he seemed to be devoured by an inner flame, and he projected himself into music like a comet into space. He simply threw himself headlong into it, and gave all there was in him.” I imagine Liszt, sitting elegantly erect, while playing the music with his whole body.

Piano technique has a long and rich history. During Bach and Mozart’s time, the keyboards were light to the touch. Performers used what was know as the “finger action” school, where the arms were relatively fixed, and the fingers skittered along. As the piano evolved with a wider range of volume, the touch became heavier. Pianists and composers such as Chopin and Liszt began to use the weight of the arm, playing with a supple wrist; this became known as the “arm weight” school of technique. I love the description that Amy Fay, a student of Liszt, wrote in 1902, “When Liszt played he seemed to be devoured by an inner flame, and he projected himself into music like a comet into space. He simply threw himself headlong into it, and gave all there was in him.” I imagine Liszt, sitting elegantly erect, while playing the music with his whole body.

Over the years, my fingers have become more and more sensitive, to the point where I swear they have developed beyond touch into vision. They have a depth of nerve endings, an acute sense of touch. When I compose music, I sink into the tactile feel of the score paper and the scratch of the pencil point into the paper. I run my finger tips on the back of the page; they read the pencil indentations as a kind of magical musical braille. Even erasing the notation errors – the rub of the end of the pencil, the small eraser castings – all this, a sensual relationship to composing.

My finger lust has spread in all directions. Since adolescence, I have knitted or crocheted, loving the way the yarn wound around my right index finger, slipped it in and out of clicking needles. Recently, I became fascinated with the various weights and textures of wool, and then, the consummate deliciousness of cashmere, thin, durable and much too expensive to buy. I found old cashmere sweaters at the thrift shop, and slowly undoing the side seams, I unraveled the yarn into glowing balls. I was, I confess, obsessed with the ease of this wealth of yarn and I made fingerless gloves, hats, scarves, and finally large cashmere blankets until my family begged me to stop.

the way the yarn wound around my right index finger, slipped it in and out of clicking needles. Recently, I became fascinated with the various weights and textures of wool, and then, the consummate deliciousness of cashmere, thin, durable and much too expensive to buy. I found old cashmere sweaters at the thrift shop, and slowly undoing the side seams, I unraveled the yarn into glowing balls. I was, I confess, obsessed with the ease of this wealth of yarn and I made fingerless gloves, hats, scarves, and finally large cashmere blankets until my family begged me to stop.

Some years ago I was introduced to drawing with pastels. This is one of the few art forms that you actually hold the color between your fingers and not on the end of the brush. The pastels come in varying grades – from cool and edgy to an almost crumbling softness. The colors are brilliant, and tempt me to taste them with my tongue. I hold myself back, and satisfy myself with the scratch or the knock of the pastel, and the spread of the color on paper. This is truly the height of finger decadence.